Never before in history were so many people required to make decisions so often and of such far-reaching consequences. Where only a handful of wise men used to choose for everybody else, today we’re all decision makers. From the CEO to the junior programmer, everyone’s decisions can send ripples across the globe. We have to learn when and how to decide.

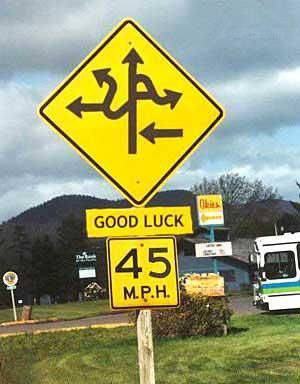

See just how significantly mentions of “decision” have increased since the outset of World War II.

Times when our days were pre-defined, we knew how to crank a widget and how many we were expected to crank to make a day’s pay, are over. Many of us in IT and elsewhere work with systems used by millions, where one bad decision could start mayhem. Welcome to the twenty first century - the age of empowerment and decisions.

decision noun A conclusion or resolution reached after consideration.

I especially like the bit saying “after consideration”. Without proper consideration a decision is a gamble taken at the mercy of mere chance. Consideration requires data - facts, figures, the knowns and the unknowns, and enough of it to make a decent judgment. Nobody said this better than Sherlock Holmes:

It is a capital mistake to theorise before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.

Sherlock Holmes, Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

But we can’t be sitting there all day, collecting facts, while the world moves on. Our competitors surely will come up with something that’ll sweep the rug from under our feet and before we know it we’ll be out of business!

Not necessarily.

Nowhere are timely decisions so important as in the military. Making one too early will give your enemy ample time to prepare. Making it too late will have you overrun by their forces. In either case lives will be lost and destruction will ensue. General Colin Powell, former United States Secretary of State and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff says decisions should be made as late as possible, but not later.

Don’t rush into decisions - make them timely and correct.

Time management is an essential feature of decision-making. One of the first questions a commander considers when faced with a mission on the battlefield is “How much time do I have before I execute?” Take a third of that time to analyze and decide. Leave two-thirds of the time for subordinates to do their analysis and make their plans. Use all the time you have. Don’t make a snap decision. Think about it, do your analysis, let your staff do their analysis. Gather all the information you can. When you enter the range of 40 to 70 percent of all available information, think about making your decision. Above all, never wait too long, never run out of time.

In the Army we had an expression, OBE—overtaken by events. In bureaucratic terms being OBE is a felonious offense. You blew it. If you took too much time to study the issue, to staff it, or to think about it, you became OBE. The issue has moved on or an autopilot decision has been made. No one cares what you think anymore - the train has left the station. [emphasis mine]

Colin Powell, It Worked for Me

Further down Powell shares the steps of collecting data:

- tell me what you know

- tell me what you don’t know

- tell me what you think

- always distinguish which from which

Colin Powell, It Worked for Me

These should be printed out on large sheets, posted next to every manager’s desk, facing anybody coming in with a report or request.

Return to the world of software, where bad decision-making may not kill anybody, but “merely” derail companies, sending hordes of people into unemployment. Any sort of Agile methodology preaches making important decisions at the right time.

- what is the next most valuable thing we should build?

- whom are we building this for? what problem are we solving?

- how will we measure success?

- what are we not going to build?

- when should we release this to users?

The worst thing one can do is what, unfortunately, comes most naturally to programmers: jump straight into coding. Programmers hate discussing, debating and researching. They want to code already!. Which leads to messy, unwanted products, delivered too late to the wrong people.

Take time to ask questions, research answers and make decisions when they need to be made.

- Order your stories, use cases or requests into a backlog, find out which of them are the most important and take the time to decide on how to build those correctly. Postpone any decisions on the remaining items until the first ones get done. Delivering them will change the value of all the other requests and spending time debating things other than immediate work will likely turn to waste.

- Be very open about what you don’t know. Not sure how a business process looks like? How to work with some technology? State it explicitly, refuse to accept the story into the iteration and create a spike instead. This should allow you to spend a time-boxed amount of work on researching missing pieces. In our current process we even created a specific type of sub-task that represents Questions and Concerns, just to have them prominently visible.

- Prototype with proofs of concept. Building any serious piece of software is a test for how suitable the chosen technology is. Start out by building a minimal, full-flow, disposable Proof of Concept piece that will test the critical portions. Put some pressure on it to see how it scales, so that if it fails, it does so early. And by the way: make sure everybody is aware that it’s disposable and will be built again correctly, right after disposal.

Keep asking yourself whether you have enough data and work to verify whether what you think you know is true. Learn and practice how to make decisions. If you avoid them, somebody else will step in and their decisions may not be to your liking.

*[CEO]: Chief Executive Officer