The whole is greater than the sum of its parts—that’s not true. Not universally, at least. Science has known this since the 19th century, that a proper team working together will often deliver less, and of lesser quality, than if the same individuals were working on their own. It’s high time we question the holy grail of “teamwork” to see exactly where it works and where it fails.

I had an eye-opening moment reading Professor Richard Wiseman’s beautifully practical book 59 Seconds: Think a Little, Change a Lot:

In the late 1880s, a French agricultural engineer named Max Ringelmann became obsessed with trying to make workers as efficient as possible. (…) One of Ringelmann’s studies involved asking people to pull on a rope to lift increasingly heavy weights. Perhaps not unreasonably, Ringelmann expected people in groups to work harder than those on their own. But the results revealed the opposite pattern. When working alone, individuals lifted around 185 pounds, but they managed only an average of 140 pounds per person when working as a group. [emphasis mine]

How is that possible? It’s due to diffusion of responsibility:

When people work on their own, their success or failure is entirely the result of their own abilities and hard work. If they do well, the glory is theirs. If they fail, they alone are accountable. However, add other people to the situation, and suddenly everyone stops trying so hard, safe in the knowledge that though individuals will not receive personal praise if the group does well, they can always blame others if it performs badly. [emphasis mine]

Lest you think this applies only to physical work—not at all. It’s the same for blue- and white-collar jobs, physical and creative alike, and across cultures:

Ask people to make as much noise as possible, and they make more on their own than in a group. Ask them to add rows of numbers, and the more people involved, the lower the work rate. Ask them to come up with ideas, and people are more creative away from the crowd. It is a universal phenomenon, emerging in studies conducted around the world, including in America, India, Thailand, and Japan.

Our experience with teamwork

My manager once said in a loose conversation “remember how we were thirty people total? I’ve a feeling we got much more work shipped back then than we do now with 200 people”. Can we test his hypothesis? Can we measure it? Hardly, since to measure correctly would require lots of metrics which we never have nor probably ever will collect.

My personal, best experience with teamwork was in preparing several conferences for Toastmasters in Poland, from the country-scale Toastmasters Leadership Institute to the half-continent scale of the biannual District 95 Conference. All of those teams truly rocked.

- everyone had their own, individual space of responsibility. I did the website and all of IT—if I blew it, I had myself to blame.

- we all respected boundaries. I had the final say on the website format and content, but I might’ve merely expressed my opinions on marketing.

- we worked individually, collaborated on a case by case basis as needed and met every few weeks for two hours total to synchronize.

- we were all volunteers with no formal ties, so the two or three persons who couldn’t keep pace with the rest were promptly removed and replaced.

Contrast that with the reality of Scrum or any other Agile teams in a typical company—large and small:

- you’re supposed to share responsibility for the work; all code is everyone’s code.

- every sprint you’re asked to spend a half-day to a day in meetings, drilling into everyone’s performance (also called a “retrospective”) and collectively brainstorming the work scope (known as “sprint planning”).

- everyone is on some contract and even in countries were it’s legally easy to fire someone, it’s still psychologically and organizationally taxing.

I did way too many “sprints” like these, and I’ve been in every role: developer, product owner, scrum master, team leader. Every single time people were dying to get out of the meetings and get back to doing productive work on their own. This never worked the way it was supposed to.

Agile is simple, but it’s not easy

The traditional response to “Agile doesn’t work” is usually that, to the contrary, it does, you’re just not “agile enough” or you have diverged from Scrum. That indeed, it’s hard to do agile right and it requires practicing all the great virtues of discipline, courage etc.

Just because some people can finish an IronMan race in 8 hours, that doesn’t mean everyone can, and in fact, very few people will ever be able to complete the distance in any time. It’s a very personal experience, of talent, character and choices, just like work style.

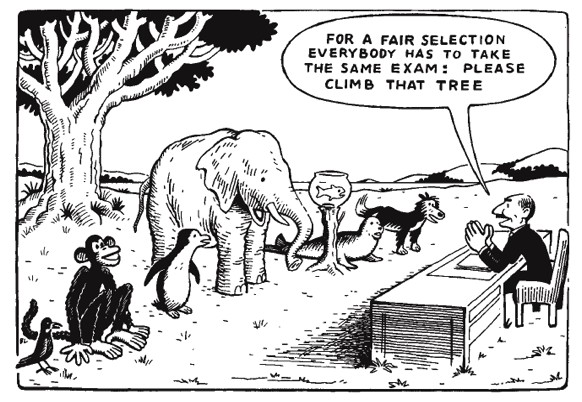

Why then do we continue to try and swim upstream? Work against human nature?

The solution to fight the western world’s epidemic of obesity is not to ask people to be more disciplined with their diets, but to find out what the natural eating habits of people are and to create food that accounts for them and is healthy. Starting with less sugar and processing would already fix the most outstanding issues.

At work, instead of asking people to “try harder”, study them. Find out what turns them on or off, and change the work environment to account for it. Are they not empathetic enough? Perhaps that’s because we’re not built for empathy in large groups. Try making the organization smaller.

“You’re lucky you’re only 50 people… We’re 300, we could never work that way.” We’re 50 on purpose, we could be 300 too.

— Jason Fried (@jasonfried) February 16, 2016

I look back at some thinking I did years ago on teams and realize now I got it only half-right. Yes, teams need to share goals, otherwise there’s no point in calling them “teams”. But “sharing work” is not about collectively executing tasks—that’s counterproductive. It’s about agreeing on outcomes where many individual streams of responsibility come together and yes, we can and should confront anyone who doesn’t deliver their portion.